A Growing Blind Spot: Microplastics and the Future of Brain Health

Floating in our air, sitting in our food, and bottled in our water

Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases are rising at a pace that should make all of us uneasy. We frequently talk about aging populations, genetics and better diagnosis. Those factors matter. But what if we are missing something hiding in plain sight. What if part of the story is floating in our air, sitting in our food, and bottled in our water. Enter microplastics.

For years microplastics were framed as an environmental problem. Harmful to oceans, fish and wildlife. A threat to ecosystems far away from our own bodies. That framing is no longer holding up. Recent studies now show that tiny plastic particles are not just out there. They are in us. In our blood. In our organs. And strikingly, in our brains.

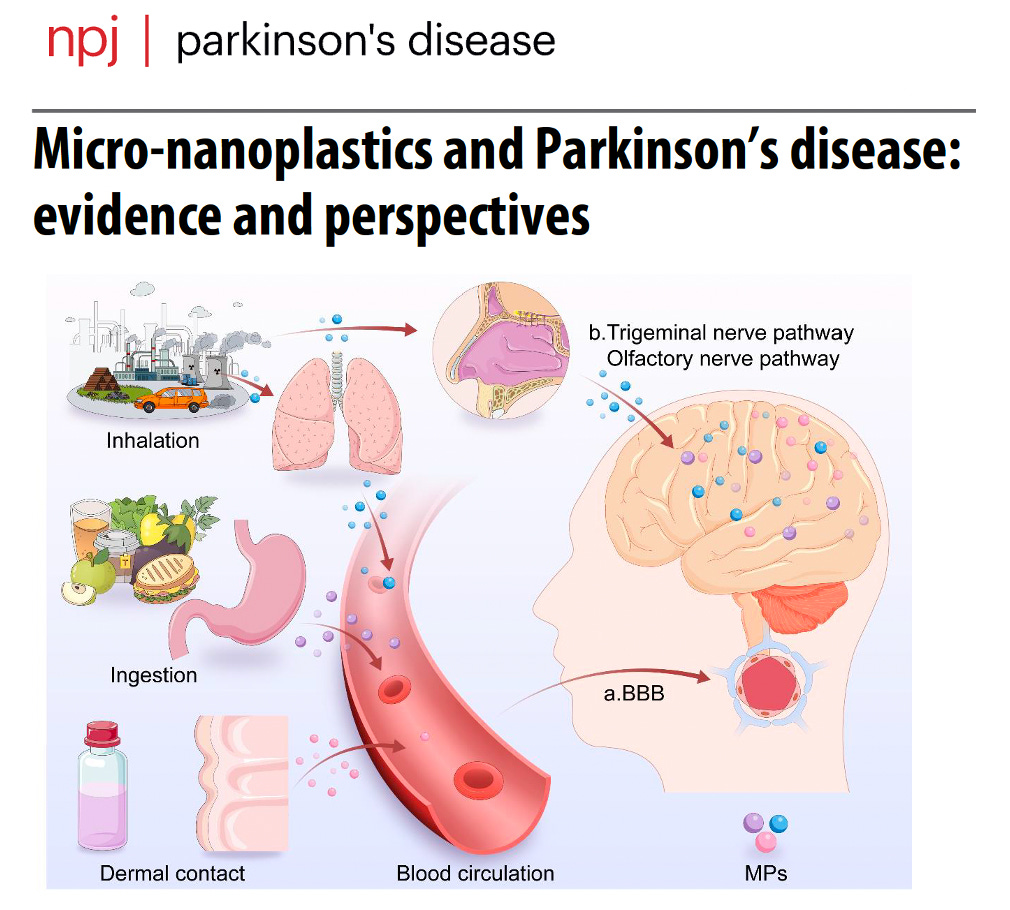

Microplastics are fragments of plastic smaller than a grain of rice. Nanoplastics are even smaller, thousands of times thinner than a human hair. These particles are created as plastics degrade from packaging, clothing, tires, bottles and countless everyday products. We ingest them, inhale them and likely absorb them through skin contact. For a long time, the assumption was simple. Most of these particles pass through the body and exit without consequence. That assumption is now being challenged.

One recent human study examined brain tissue from people who had died over the past decade. The investigators found microplastics and nanoplastics embedded in brain tissue at concentrations higher than in the liver or kidney. Even more concerning, the levels appeared higher in individuals who had dementia. This does not prove cause and effect. However, it does raise a question that is hard to ignore. Why would plastic particles preferentially accumulate in the brain, and what are they doing once they get there?

Animal and cell studies are beginning to offer clues. In models of Alzheimer’s disease, exposure to microplastics worsened memory problems, increased inflammation and disrupted the connections between brain cells. In Parkinson’s disease models, these particles promoted misfolding of alpha synuclein, the same dysfunctional protein that clumps together in Lewy bodies. The particles also affected mitochondria, the energy factories of neurons, as well as activated immune cells in ways we recognize as potentially harmful to the brain.

Another study measured microplastics directly in the blood of people with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease. The levels were higher than in similar individuals without Parkinson’s. Additionally, certain types of plastics were particularly enriched. When those same plastics were tested in laboratory models, they injured dopamine producing neurons, and increased toxic protein changes known to be linked to Parkinson’s pathology.

Again, this does not mean microplastics cause Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease. However, it does suggest they may act as accelerants. Small, repeated hits layered onto aging, genetic vulnerability, inflammation and other environmental exposures could be very bad.

If this sounds familiar it should. We have been here before. For decades air pollution was dismissed as a lung issue until evidence forced us to confront its role in heart disease, stroke and dementia. Pesticides were once viewed as agricultural tools until links to Parkinson’s disease became undeniable. In each case, the pattern was the same. Early signals were easy to ignore simply because they did not fit existing frameworks. Microplastics may represent a similar blind spot. They cross the blood brain barrier. They interact with immune cells. They disrupt mitochondria. They interfere with protein handling systems important to keeping neurons healthy. These are not fringe mechanisms. They sit at the very center of what we believe drives neurodegenerative disease.

There is also a timing issue that should concern us. Plastic production has exploded over the past 50 years. Neurodegenerative diseases have risen dramatically over the same period. Correlation is not causation. But when biological plausibility lines up with exposure trends and with early human data, it deserves our serious attention.

What should we do now? First we need humility. We do not yet know the true impact of microplastics on brain health. Large long term human studies are urgently needed. We need better ways to measure exposure to understand how particles enter and exit the brain and to identify who is most vulnerable. Second, we need curiosity instead of dismissal. This is not about panic or fear. It is about asking whether a modern ubiquitous exposure could be quietly shaping risk. Third, we need prevention-based thinking. Even before all the answers arrive, there are reasonable steps that we can take to reduce exposure. Less reliance on single use plastics. Safer food and water storage. Better filtration. These steps will likely carry broader health benefits, regardless of their ultimate link to neurodegeneration. Finally, we need to expand how we think about Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. They are not just brain disorders. They are whole body disorders shaped by environment, biology and time. The brain does not live in isolation from the world around it.

If microplastics turn out to be part of this story, the implications are enormous. Not just for treatment, but for prevention. Not just for individuals, but for public health policy. The question is not whether plastics are everywhere. We already know they are. The question is whether we are ready to take an honest look at what that means for our brains. Ignoring the possibility would be the real blind spot.

Selected References:

1. Lin L, Li J, Zhu S, et al. Micro-nanoplastics and Parkinson’s disease: evidence and perspectives. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2026;12:Article 272. doi:10.1038/s41531-026-01272-4. Image above from the recent review article by Lin et. al.

2. Nihart AJ, Garcia MA, El Hayek E, et al. Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nat Med. 2025;31(4):1114-1119. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03453-1

3. Dua K, Dhanasekaran M, Paudel KR, et al. Do microplastics play a role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases? Shared pathophysiological pathways for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;500:Article 05428. doi:10.1007/s11010-025-05428-3

4. Liu C, Zhao Y, Dao JJ, et al. Food-borne polystyrene microplastic exposure exacerbates cognitive deficiency via enhanced neuronal synaptic damage and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Toxicology. 2026;520:154371. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2025.154371

5. Xu Z, Huang X, Zhu Z, et al. Elevated blood microplastics and their potential association with Parkinson’s disease. J Hazard Mater. 2025;500:140431. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.14043

1

Michael: Thank you for the thoughtful overview on plastics and PD. We think alike.

Nice